The Dark Side of Stock-Based Compensation

How management deeds while shareholders bleed

Stock-based compensation, often called SBC, has become a very important part of the modern pay structures, especially among startups and publicly traded companies. Often seen as an incentive to attract the best talents, it has become a twisted tool designed to drain value from shareholders to management.

Since few investors fully understand stock-based compensation, this article aims to explain what it is, how it works, how it impacts a company’s financials, and the risks of investing in companies that rely too heavily on it.

Most of the data used in this article are based on 2 sources:

A very detailed article by Morgan Stanley

Marketscreener.com (you can access the site through the following link. Please note it is an affialiate link so it is a way to support this newsletter)

What is stock-based compensation?

Stock-based compensation is the practice of paying employees or directors with equity in the company rather than receiving only cash salaries / bonuses.

There are many forms (stock options, performance shares, restricted stock units, …) but the acquisition of shares is often linked to different conditions such as specific results (growth, product development, etc) and/or staying in the company.

Companies use it for different reasons but the main ones are:

It aligns employee and shareholder interests. By giving employees equity, their success becomes directly tied to the company's stock performance, incentivizing them to act in shareholders’ best interests

It conserves cash while funding growth. Instead of paying high salaries or bonuses in cash, companies can use equity, which is especially valuable for startups or growth-stage firms trying to preserve capital. However, issuing new shares can dilute existing shareholders

It attracts and retains top talents. Stock-based compensation serves as a powerful recruitment and retention tool. Equity awards (often tied to multi-year vesting schedules) encourage employees to stay and contribute to long-term success

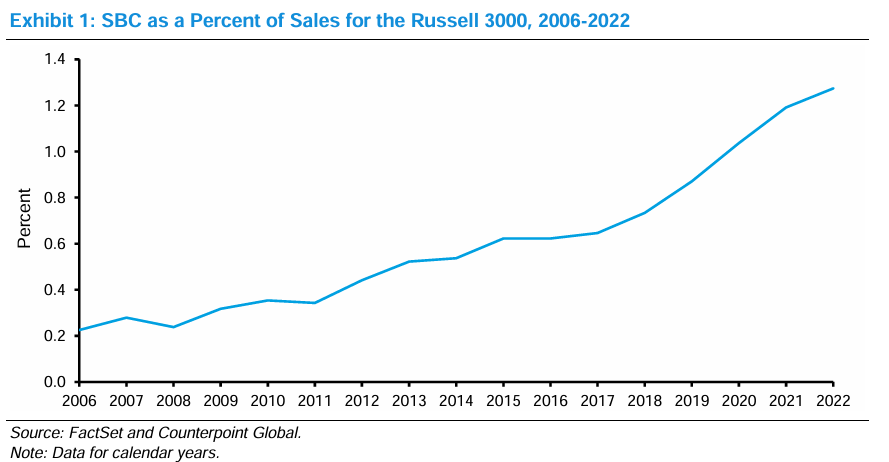

Stock-based compensation is being used more frequently, with its adoption growing rapidly across industries.

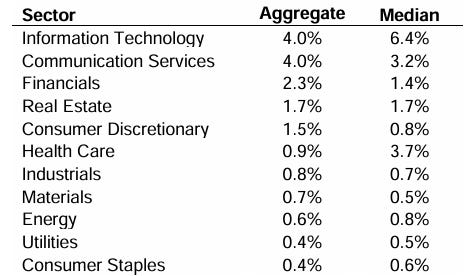

While stock-based compensation is being used more widely across industries, there are significant disparities by sector. Software companies, in particular, make the most aggressive use of it (often to the point of excess) with SBC expenses averaging nearly 10% of revenue (Yes, revenue and not profit).

The limitations of SBC

Many companies report both GAAP and non-GAAP earnings, with the latter often excluding SBC on the grounds that it is a non-cash expense. While technically accurate, this treatment can obscure the real cost to shareholders. Issuing new shares dilutes existing ownership, and over time, this dilution imposes a significant economic burden on shareholders, even if it doesn’t show up as an immediate cash outflow.

Excluding SBC from adjusted earnings can significantly distort a company’s true profitability. For example, a business may report strong non-GAAP operating margins, yet once SBC is factored in, those margins may shrink substantially or even turn negative. The same applies to FCF, another commonly cited non-GAAP metric, while FCF may appear robust on paper, it can be misleading if a large portion is effectively being used to compensate employees via equity.

This artificial reporting can cause investors to overestimate the operational strength and efficiency of a company. Worse, an overreliance on adjusted figures may change a corporate culture where dilution is brushed aside and compensation becomes decoupled from operational and commercial performance. In more extreme cases, executives may benefit disproportionately from generous stock awards, enriching themselves while the long-term cost is payed by shareholders through reduced ownership stakes and diluted earnings power.

Conclusion

While SBC can be a powerful tool for aligning employee and shareholder interests, investors should remain vigilant. In many cases (especially among high-growth software companies in the US market) SBC has evolved beyond a talent retention strategy and become a mechanism for enriching top executives, often at the expense of shareholders.

Ultimately, it is the shareholder who pay the bill. The common defense is that a few percentage points of dilution are negligible compared to a 100% rise in stock price. But it reflects a short-term mindset. This argument tends to resonate with investors focused on immediate gains, but it ignores the long-term reality: when excessive SBC continues unchecked, even strong stock performance can be undermined by persistent dilution. Over time, the fundamentals catch up, and valuation multiples compress leaving shareholders with a smaller piece of the pie.

In short, SBC is not inherently bad, but its misuse can be costly. A cautious, critical approach, especially when analyzing companies with high SBC as a percentage of revenue or free cash flow, is not just prudent, it is essential for protecting long-term returns.

Tell me what you think of SBC in the comments!